Cases

Functions, Meanings and Labels

The eight main cases of Quenya (common, genitive-partitive, genitive-adjective, dative, instrumental, locative, ablative and allative) are used in different syntactic functions:

- to mark obligatory constituents with verbs and adjectives (subject, object, complement; here belong also certain uses in constructions like the common-and-infinitive, common-and-participle, etc.);

- to complement prepositions;

- to mark attributive modifiers (the main function of the genitive);

- to mark various adverbial modifiers (here belong also certain uses in constructions like the locative absolute);

- a few other, idiomatic uses.

In the overview below, the most important uses of each of the cases are listed, organized by syntactic function. The prepositions are treated separately, →31.

Common

The common case combines functions of historically separate nominative and accusative cases.

As Nominative for Obligatory Constituent with Verbs

The nominative is the case used for the subject of a finite verb (and any modifiers that agree with it, →27.7).

Predicative complements with linking verbs (→26.8) agree with their subject (→27.7), and thus also stand in the nominative.

Other Uses of Nominative

The nominative is used with some most common prepositions as there default choice (→31).

The nominative is also used in bare lists (→26.29), including entries in dictionaries.

For the nominative used in apposition to a sentence, →27.14.

The nominative is also used as a vocative: in calls or summonses to attract the attention of a person nearby, or of a god; in addresses, to acknowledge or maintain contact with some person nearby.

Note

When vocative stands in apposition to a noun, the case of that noun is applied, however.

As Accusative for Obligatory Constituent (to Complement Verbs)

The accusative is the standard case for the direct object with verbs which take an object (→26.3).

The following verbs (→26.12) take a direct object and a predicative complement that agrees with that object (and thus also stands in the accusative; this is often called a 'double accusative').

The accusative is also used in the accusative-and-infinitive (→51), the accusative absolute (→52) and accusative-and-participle constructions (→52).

As an Optional Constituent (Adverbial Modifier)

Time when, or within which, is expressed by either locative or accusative:

umbe nin i hríve nauva urra si loa[PE22/168]. I have a feeling that winter will be bad this year.

Accusative can also denote the spatial measure (how long? how broad?), especially with numerals:

talion lempe halda ná i·ando[translated; TAI/150]. Five foot high is the door.

Genitive

The main function of the genitive is at the level of the noun phrase, to mark attributive modifiers (i.e. expressing various relations between (pro)nouns/noun phrases). It is also used to mark some required constituents (complements) with adjectives, and functions in a few adverbial expressions.

Quenya distinguishes two genitival cases: genitive I or partitive and genitive II or adjective1.

As Modifier in a Noun Phrase: the Attributive Genitive

The genitive is used particularly within noun phrases, to mark a noun phrase or pronoun as modifier of a head (→26.18). Traditionally, many different categories within this attributive genitive use are distinguished; the most important of these are given below:

- The genitive of possession denotes ownership, belonging, etc.;

- The genitive of origin denotes the origin, offspring, source, etc. of the head;

- With nouns that express an action ('action nouns', →23.6), the genitive is used for the subject or object of that action — genitive of the subject (or 'subjective' genitive) or of the object (or 'objective' genitive);

- Other relations between nouns: material/contents, price/value, elaboration, etc.

Genitive of possession distinguishes alienable (which can be given away or lost) and inalienable (perpetual and inherent to the head) possession. Concepts comprising inalienable possession include:

- body parts:

rámar aldaron,hon maro; - part-whole relations:

tyulma ciryo,aicasse Taniquetildo; - kinship terms:

amille Hristo,indis i·ciryamo; - various social relations:

ingwe ingweron,aran zindaron; - attributes:

Vorondo voronwe,alcar Oromèo; - products originating from the head:

yáve móno,óma tário.

Generally these categories are expressed with genitive partitive, while the rest — alienable relations — with genitive adjective: Vardava tellumar, róma Oroméva.

Genitive of origin marks the location where the modifier originated from, or its creator (who might not be in its possession), or its author:

- location:

Calaciryo míri,Eldar Malariando; - creator:

róma Oromèo,i·coimas Eldaron.

Genitive of origin is expressed with genitive partitive, but its locational function is complementary to ablative, particularly if the noun phrase already has a modifier in genitive of another function: menelluin Írildeo Ondolindello.

Genitive of composition describes the relation between two nouns as a part to its whole:

- material or substance:

yuldar miruvóreo; - content:

parma mittarion,aure veryanwesto; - individual elements:

yénion yéni; - source:

astali hruo.

Genitive of subject, marked by genitive I, denotes the subject of a verbal noun: Túro matie masta, nero carie cirya. Note that the action can sometimes be implicit: Ráno tie path of the Moon ('path taken by the Moon').

Genitive of object (genitive II) describes the affected patient of the action: Nurtale Valinóreva, ciryava carie. Note that gerund can take a direct specific object in accusative like a verb. In that case, the object must follow2 it: carie cirya making of a (specific) ship.

Determiner Genitive and Descriptive Genitive

While the functions listed above are useful, in practice they don't cover a multitude of border cases which we label here as descriptive. Most grammars treat it as a homogenous category with only vaguely defined function, but we can distinguish a few categories within it, responsible for naming, comparing and describing:

Classifying genitives are used to name certain objects, where the dependent clearly restricts the denotation of the head noun: Nand' Gondoluncava, hwesta zindarinwa, Eruva lisse.

Such genitive is semantically most closely related to adjectives and loose compounds: farea nasto, meneldea Eru, Ambarmetta, Elennanóre. Therefore it typically employs genitive II3.

Metaphorical Genitive is used to describe an object, experience, state etc. in terms of another one: yéni únótimë ve rámar aldaron. Structurally these genitives behave like determiner genitives from before, but the dependent is very clearly not specific. They do not have the function of a typical determiner (i.e. the referential anchoring of a referent), but rather, they evoke a certain typical property.

In contrast to metaphorical genitives, generic genitives are not used to compare a referent in terms of another referent (or the referent’s properties) but to describe a specific referent by setting it in relation to its kind: lambe Eldaron.

Genitive II and Loose Compound

Tip

Essentially, adjective genitive only differs from N + N sequences in containing the marker -va. There are two main factors determining the presence or absence of -va in N + N sequences (given that both allow for a possessive construal), i.e. the animacy and the referentiality of the dependent.

Adjective genitive still contains some degree of referentiality, in any case more than in expressions with loose compounding. For this reason, rácina [arquenwa macil] is more likely to refer to a specific knight than rácina [arquen macil].

Furthermore, animate dependents are usually realized with the -va, while inanimate dependents prefer the loose construction. In many cases. however, animacy does not determine categorically whether a genitive or an N + N sequence is used, but rather the statistical preference (i.e. frequency) of the two constructions.

Genitive Gradience

Gradience in grammar is usually characterized as the phenomenon of blurred boundaries between two categories. When it comes to genitive and the use of genitive I over genitive II, we distinguish two sources for gradience: gradience of the semantic features and gradience as a mismatch in the meaning–form mapping.

Gradience of the semantic features arises from natural ambiguity of some interpretations:

Eldar Malariandothe elves of (from) Beleriand [genitive of origin] andEldar Malariandévathe Beleriand elves [classifying genitive] are for all purposes the same.

The choice then comes as mostly esthetical, but some difference in meaning might still be implied:

yuldar miruvóreodraughts (made) of mead [genitive of composition] andyuldar miruvórevamead draughts, draughts sweet like mead [classifying or metaphorical genitive].

Mismatch mapping is a very late phenomenon when Quenya stopped being a colloquial language. It surfaced as a confusion between semantics of genitive I and II and consequent displacement of the latter.

Tip

As a rule of thumb if you are in an muddy case where it is difficult to decide between genitive I or II, consider whether a dependent is conveying a reference (genitive I) or describing a property (genitive II):

octe porceoan egg of (a specific) chicken;octe porcevaa chicken egg (and not a duck egg).

As Obligatory Constituent

With Adjectives

The following adjectives (often related in meaning to the verbs regularly taking adverbial modifiers, especially with partitive sense) are complemented by a genitive: 'filled with', 'released from', 'free from', etc.

The genitive of comparison is used to complement comparatives:

arimelda na ilyaron[PE17/57]. She is dearest of all.

For more details on comparatives and their constructions, →32.

With Numerals

From nelde three onwards, a preceding noun or noun phrase stand in genitive I plural: elenion nelde three stars. Note that in the late use it was substituted with accusative: eleni nelde three stars. For details on agreement of numerals, →26.TBD.

As Predicative Complement or Prepositional Complement

Many of the attributive uses of the genitive (→30.above) also occur as predicative complement with linking verbs.

The genitive of quality, used to express a certain characteristic or manner of being, occurs exclusively in this way:

neri ú nati nostalèo mare[translated; PE15/32]4. Men are not beings good by nature.

Similarly, attributive uses of the genitive may occur after certain prepositions (→31.8):

Aina Wende mi Wenderon[VT44/12]. Holy Virgin of virgins.

As an Optional Constituent (Adverbial Modifier)

Sometimes verbs take genitive I in its partitive function to underline separation:

- verbs meaning 'remove from', 'rob of', 'free from' etc.:

Varda ortane máryat Oiolosseo,lunces macilya vaileo5; - many verbs expressing sensorial or mental processes, to denote a source of stimulus:

hlassenye·s Vardo6.

Note

To describe the direction, genitive is substituted with ablative: tentane Melcorello.

Some verbs permit the genitive of cause to express the origin or reason for that action: síla Ráno7.

Dative

The main function of the dative is to mark non-obligatory (adverbial) modifiers. It is also used to mark some required complements with verbs.

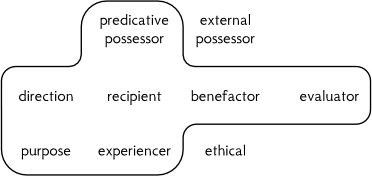

Figure 30.1: Implication map: dative case of Quenya

- recipient:

ámen anta síra ilaurea massamma[VT43/12]. Give us this day our daily bread. - benefactor:

sí man i yulma nin enquantuva?[LotR/377]. Who now shall refill the cup for me? - predicative possessor:

umbe nin i hríve nauva urra[PE22/168]. I have a feeling that winter will be bad. - experiencer:

ece nin care sa[VT49/20]. I can do that. - evaluator:

i jarma ú ten ulca símaryassen[VT49/8]. The left hand was not to them evil in their imaginations. - direction:

mi cemen raine i hínin[VT44/34]. On earth peace, good will toward men. - purpose:

vanda sina termaruva Elenna·nóreo alcar enyalien[UT/305]. This oath shall stand in memory of the glory of the Land of the Star.

As Obligatory Constituent (to Complement Verbs)

As Indirect Object

The dative is used to express the indirect object or the recipient (Y) with the following types of verbs (X indicates a direct object in the common-accusative, where present):

- verbs meaning give, entrust, etc.;

- verbs meaning say, tell, report, etc. (usually with direct or indirect statement, →41.3);

- most verbs meaning command, order, advise etc. (usually together with an infinitive, →51.8);

- most verbs meaning seem, appear, etc.

The dative as indirect object, or experiencer, complements the following impersonal verbs (→36.4-5), usually together with an infinitive (→51.8) (Y marks the dative):

eceit is possible for Y (to do something);olaY dreams (of something);h·oreY feels an urge (to do something);moa8 Y must (do something);naiit may chance for Y (to do something);

Dative of the Possessor

The dative of the possessor is used to complement 'existential' ná and ea (there is, →26.10), denoting possession, belonging, or interest. On the difference between this dative and verbs of possession (same, harya, etc.), → TBD.

As an Optional Constituent (Adverbial Modifier)

Referring to Things or Abstract Entities

The dative is very frequently used to express optional adverbial modifiers (→26.14). It marks nouns referring to things or abstract entities in various kinds of adverbial modifiers.

The dative of cause expresses reason or cause.

The bare dative of place may be used to express the direction whereto action takes place, as a short form of allative:

lendes pallan i sír[PE17/65]. He came to a point far beyond the river.

Referring to Persons

The dative of advantage and dative of disadvantage are used to indicate the beneficiary (or opposite) of an action; they express in or against whose interest an action is performed:

Ilu Ilúvatar en cáre eldain a fírimoin[MQ: LR/63]. The Father made the World for Elves and Mortals.

The dative also marks the person from whose perspective or vantage point the action is perceived:

tulil márie nin[PE22/158]. You come happily for me.

Instrumental

The main function of the instrumental is to mark non-obligatory (adverbial) modifiers.

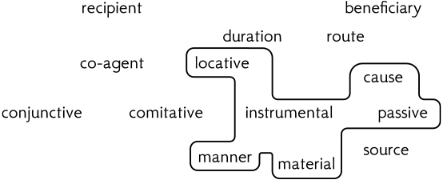

Figure 30.2: Implication map: instrumental case of Quenya9

- instrumental:

antanenyes parmanen[PE17/91]. I presented him with a book. - material:

erulissenen quanta[VT43/26]. Filled with grace. - manner:

norne lintieryanen[PE17/58-59]. He ran as swiftly as he could. - passive:

turún' ambartanen[UT/138]. By doom mastered. - cause:

Eru-indonen[PE22/165]. By the will of God. - locative:

tintilar i eleni lírinen[LotR/377]. The stars tremble in her voice.

As an Optional Constituent (Adverbial Modifier)

Instrumental case, as the name implies, most commonly marks the instrument or means by which an action is carried out: built with a hammer, painted with a brush, fought with fists.

The instrumental of material is closely adjacent to it, and is used to complement transitive verbs and related adjectives to describe the material used in action: built with stone, rich with spoils, fraught with sorrows. Note the difference: filled with water (instrumental of material), but full of water (genitive of material).

The instrumental of manner describes the manner in which an action was carried out, particularly with abstract nouns: carry with weariness, shine with golden light, give in measure10.

The instrumental of agent is used in passive constructions to denote the agent of the action: executed by the king, heard by the audience, blamed by the wicked.

While the instrumental of agent is usually employed for voluntary actions of animate nouns, similar instrumental of cause describes the circumstances in which an action happened, sometimes tangentially, and generally can be substituted in gloss with because of: disabled by a wound, bent with the sails11.

The instrumental of location describes location or other intrinsic relations linked to the manner or source of an action, typically of intransitive verbs, and is generally translated with in, on: fall in the wind, cloack in veils, fluttering on the wings.

Locative

The main function of the locative is to mark non-obligatory (adverbial) modifiers describing the scene of the action, generally pointing out where or when the action is happening.

Spatial Locative

The locative describes a general spatial relation. We can postulate the basing meaning as12:

Rule 1

The figure is located close to the ground.

The exact position therefore is either not relevant, or easily accessible through context. The use of specific spatial adpositions, like mi in or to on (→ TBD), emphasizes the particulars of the relation and can highlight any deviations from the default assumption, thus serving to cancel unwarranted implicatures:

Implication:

- The figure is in contact with the ground.

- The figure–ground relation is canonical.

- The ground supports the figure against gravity.

The canonicity of the relation is determined pragmatically: a plate is on a table rather than under it, while an apple is in a bowl rather than at it.

To provide some examples:

-

the locative conveys the notion of being within a containment:

i fairi néce ringa súmaryasse ve maiwi yaimie[MC/222]. The pale phantoms in her cold bosom like gulls wailing.

-

it denotes a surface, trodden or touched:

man tiruva rácina cirya gondolisse morne?[MC/222]. Who shall heed a broken ship on the dark rocks?

-

it signifies the dominion or territory:

Altariello nainie Lóriendesse[RGEO/58]. Galadriel’s lament in Lórien.

-

and the substance the locus is submerged into:

nicsi coitar nenesse[PE22/125]. Fish live in water.

Locative of Circumstance

As the extenstion of this meaning, the locative often denotes the circumstances, under which the action comes to pass.

This kind of locative encompasses the locative of time as well as the absolute locative (TBD).

Locative of Time

The locative of time refers to a specific moment or period:

- at which the event happens;

-

by which the event should happen.

-

qe e·kárie i kirya aldaryas, ni kauva kiryasta menelyas[MQ: PE22/121]. If he finishes the boat by Tuesday, I shall be able to sail on Wednesday.

Locative of Respect

The locative of respect may denote the particular point of view from which a statement is made. This occurs chiefly with adjectives but also with intransitive verbs, and in gloss can be substituted with with regard to:

i hyarma ú ten ulca símaryassen[VT49/6]. the left hand was not to them evil in their imaginations.

Such locative can be used for:

- parts of the body: pain in finger, blind in mind, smitten on the neck;

- qualities and attributes (nature, form, size, name, birth, number, etc.): rival in appearance, two leagues in width;

- sphere in general: terrible in battle, good in matters in which he is skilled.

The instrumental of manner and genitive of quality are often nearly equivalent to the locative of respect: men are good in nature; men are good by nature; men are of good nature13.

Locative of Manner

With abstract nouns locative of manner can be used periphrasically to describe the state:

hara máriesse[PE17/162]. Stay in happiness (or: stay happily)alalye nattira arcandemmar sangiessemman[VT44/8]. Despise not our petitions in our necessities (or: done out of necessity).

As Obligatory Complement

Some verbs take what might be a direct object in other languages as a complement in locative case:

Heru órava omesse[VT44/12]. Lord, have mercy on us.

Allative

The main function of the allative is to mark non-obligatory (adverbial) modifiers describing the goal of the motion, generally pointing out whither.

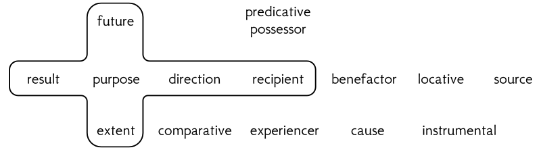

Figure 30.3: Implication map: allative case of Quenya

As a Direction of Movement

The allative describes a general directional goal of the movement.

The exact position therefore is either not relevant, or easily accessible through context. The use with a specific spatial static adposition, like nu under (→ TBD), emphasizes the particulars:

lantaner Turcildi nuhuinenna[LR/47]. the Lordly Men fell under shadow.enwina lúme elenillor pella talta-taltala[MC/222]. The old darkness beyond the stars falling.

The canonicity of the relation is determined pragmatically, and a series of directional adpositions are used instead when the context is not complicit:

unlunke naiqe yu vaile·na ar elle ha men ambostuva[EQ: PE16/146]. He pulled his sword from the sheath and drove it into the breast.

To provide some canonic examples:

-

the allative describes the motion into a containment:

eari ullier i kilyanna[LR/47]. The seas poured into the chasm.

-

it denotes a surface a movement is directed towards and comes into direct contact with:

Anar caluva tielyanna[UT/22]. The sun shall shine upon your path.

-

it signifies entered dominion or territory:

Et Eärello Endorenna utúlien[LotR/967]. Out of the Great Sea to Middle-earth have I come.

-

and generally the end point of a movement or intended destination:

hríve úva véna[PE22/167]. Winter is drawing near to us.quiquie menin coaryanna, arse[VT49/24]. Whenever I arrive at his house, he is out.

-

as well as the target of aim:

ar cé mo formenna tentanes Amanna[VT49/8]. And if (one turned face) northwards, it (left hand) pointed towards Aman.

Warning

Allative profiles the goal as the intended destination, but it does not specify whether this goal is reached or whether an agent is somewhere on the way. However, if the direction is not the goal, the allative cannot be used. To describe the directionality of the path, the adposition na towards is employed instead14.

Allative of Time

In the domain of time, the use of the allative is restricted to those expressions where both the starting point and the endpoint are mentioned. For instance, if we want to say 'from Monday to Friday', we will use the allative as in izilyallo valanyanna, but if we just want to mention the endpoint, the use of the allative is not allowed; instead, the adposition tenna until is used. Therefore, until tomorrow is translated as tenna enar16.

Allative of Purpose

Assumption

Extending the meaning of direction, allative also signifies the purpose of the action, following a frequent conceptualization: causes are origins of events, and purposes are destinations: let's go looking for food15.

For the use of allative of purpose in periphrasic future construction → TBD.

Allative as Translative

Assumption

Verbs of change like óla, virya, ahya take allative to describe a final state or result: he turned into a great scholar.

Allative of Extent

Similar to instrumental, allative can describe how an action was carried out, answering a question to what extent? to what degree?

a laita tárienna[LotR/953]. Praise (them) to the height.

As Obligatory Complement

As Direct Object

Some verbs take what might be a direct object in other languages as a complement in allative case:

verya senna[VT49/45]. I married her.Tar-Calion octacáre Valannar[LR/47]. Tar-Kalion warred the Powers.

As Indirect Object

Generally, dative denoting a recipient can be freely substituted for allative:

antane ninna[PE17/147]. He gave it to me.sin quentë Quendingoldo Elendilenna[PM/401]. Thus Pengolodh said to Elendil.

Ablative

The main function of the ablative is to mark non-obligatory (adverbial) modifiers describing the source of the motion, generally pointing out whence, and is therefore the very opposite of allative.

As a Direction of Movement

The ablative, then, is wanted to express from what place there is a starting and moving:

-

in its proper sense, movement away from:

métima hrestallo círaleave the last shore [MC/221];

-

movement out of a container, often accompanied with a preposition

et:Melko Mardello lendeMelko has gone from Earth [MQ: LR/72]et Eärello Endorenna utúlienout of the Great Sea to Middle-earth I have come [LotR/967];

-

starting point of movement:

elenillor pella talta-taltalabeyond stars falling [MC/222]

-

pointing, aiming away from:

i hyarma tentane Melkorellothe left hand pointed away from Melkor [VT49/6];

Assumption

- moving off a surface;

- to see, hear, speak etc from a spot;

Warning

Verbs of separation from the whole take genitive I: n·alalmino hyá lanta lasse from the elm-tree here a leaf falls [EQ:VT40/8].

Ablative of Source, Origin and Cause

In a more abstract sense with verbs of:

- taking, receiving from:

yello camnelyesfrom whom you received him [VT47/21]; - protecting, guarding, securing from:

áme etelehta ulcullodeliver us from evil [VT43/12]; - being afraid of [VT44/7];

Assumption

- asking, wishing, learning from;

- restraining, preventing, excluding from;

Note

Ablative of origin can also be used as an attributive modifier: Menelluin Írildeo Gondolindello Cornflower of Idril from Gondolin [TAI/193], fanwen tollillon lómealloi a dream from the gloomy islands [PE16/147]. Genitive I is more common in this role, however.

Assumption

From a common interpretation causes are origins of events arises the ablative of cause, describing the cause, reason, motive by which an action or an event came to be17.

Ablative of Time

When denoting time, the ablative carries the meaning of from, since, after. Commonly it is attended by prepositions, as et: et sillumello ter yénion yéni tenn' ambarmetta from this hour, through years of years until the ending of the world [VT44/33], but it is possible to go with single ablative18.

Ablative as Exessive

Assumption

As the opposite of translative, exessive denotes the former state or shape, out of which some other state or shape proceeds or is produced.

As Obligatory Complement

As Indirect Object

A few special verbs take second (indirect) object in ablative:

ávatyara mello roctammar[VT43/11]. Forgive us our trespasses.

Sources:

- "Descriptive genitives in English: a case study on constructional gradience" by Anette Rosenbach

- "Space Between Languages" by M. Feist

- "A Typological Study of Local Cases in EIA Languages" by B. Lahiri

- "Crosslinguistic grammaticalization patterns of the Allative" by S. Rice and K. Kabata

-

more commonly labeled in other sources as possessive or possessive-adjective. ↩

-

The system is described in [PE22/120]. ↩

-

MQ

Ar Ulmonand others would need to be changed toUlmóvawithin this system, as specifying a kind of day rather than referring to Ulmo. I treat it similarly tomar vanwa tyalien >> mar vanwa tyaliévavascillation. ↩ -

EQ

néri ur natsi nostalen máre. ↩ -

Updated from EQ

unlunke naiqe yu vaile·na ar elle ha men ambostuva. ↩ -

Not attested. ↩

-

EQ

silmeráno tindon. ↩ -

unattested. ↩

-

"A diachronic dimension in maps of case functions" by Heiko Narrog. ↩

-

also,

tanenin this way [VT49/11]. ↩ -

also,

tánentherefore [VT49/11]. ↩ -

Where figure is the described noun or action, and ground is the locus. ↩

-

Such overlap doesn't seem problematic, as it similarly exists in Ancient Greek (Accusative and Dative of Respect), Latin (Ablative and Genitive of Quality) and Sanskrit (Ablative, Instrumental, Genitive and Locative), where those are concurrent idioms. ↩

-

[PE21/79]. More on difference between allative and directive can be found in "Polysemy in Basque Locational Cases" by Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano. ↩

-

ortírielyanna rucimme might be an example of such function ("we flee for your protection"), and the use of ruce with ablative to denote the cause of fear does give some credibility to it. However, the Latin original Sub tuum praesidium confugimus has a metaphorical spatial sense 'under', hence the example cannot serve as a solid confirmation of such usage. But for typological and pragmatical reasons, as well as (weak) additional support by future function, we suggest to keep it. ↩

-

Neither ablative nor allative are attested in temporal domain, but: "

nato, towards, of space/time" [PE17/147]. ↩ -

Not attested. But

etta, unless discarded, plays into conceptualization. ↩ -

Typologically, but not attested. ↩